We’re pleased to bring you the third and final section of William Leo Coakley’s autobiographical essay (part one, part two) tracing his life and experiences in the poetry world from the mid-20th century to today. When we last left off — as they used to say on the soaps — Willie and his partner Robin were in Italy, staying with one of the stars of Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, and appearing as extras in spaghetti westerns to pay for their extended stay!

When we returned to New York, we had to get back to regular work. Robin decided to concentrate more on his writing, translating for the theatre, coaching, and teaching speech. I was off to the New York Public Library as Managing Editor of Publications, able to publish interesting books from the archives, including, it turned out, many by queer authors: Whitman, Wilde, Woolf, and Auden, among them. And Robin and I started the poetry publishing press: Helikon Press.

All this life and sex did work their way into my poetry. Two years before Stonewall, my “Invasion of the Animals” was one of the earliest explicitly sexual gay poems to be published in a major national magazine, the New American Review, as it was then called. It was an extended metaphor using the animals of the Borghese Zoo in Rome as male body parts, so it probably was able to slip by the illiterate censors of the time.

It should be said that Auden’s great poem “Lay Your Sleeping Head, My Love” had long ago been published. And even though I was never taken by Allen Ginsberg’s rambling poetry (except the elegy to his mad mother Kaddish), where would we be without the wild sex scenes and the memorable “fucked in the ass” line in his pamphlet Howl printed a decade earlier (later first published whole in the Evergreen Review)? And his publisher had the courage to fight to get ‘fuck’ back into the printed language. The victorious court battles over Ulysses and Howl enabled us queer poets and writers, like Marilyn Hacker with her beautifully crafted poems of Lesbian sex and love, to have the freedom to be completely open. I knew Ginsberg over the years, from my early days in the Macdougal Street cafes and bars (but Robin liked him better).

The enlarged cover of the Review, with my name on it, was featured in the window of old Scribner’s on 5th Avenue, and my boss, the head of the Library, saw it and went in and read the poem. All he said, straight as he was, was how much he enjoyed it. Libraries, of course, were one of the chief havens for queers in those days. The only whiff of homophobia came from the Library’s old-fashioned internal printing shop. When I brought in a photographic booklet on Ted Shawn and His Men Dancers, they muttered, unsuccessfully, about refusing to print the ‘pornographic’ photos of the almost nude dancers flying about. Of course, most of the men were gay, as Shawn himself was, even though married for many years to the great American dancer Ruth St Denis, Miss Ruth to everyone. At the turn of the last century Miss Ruth had been in a New York play with Robin’s English actress mother; and he and she were very close throughout her long lifetime.

Robin and Harfleur, Manila, Goodbye publicity photo by Layle Silbert

With Robin as my director, I first read my poetry at St Mark’s in-the-Bowery. A church fortunately has a stout pulpit, and I held on to it for dear life but I soon began to enjoy reading in public. Having won the Discovery series in 1969 I read at the Poetry Center in 92nd Street. Robin’s friend the poet and Filipino National Treasure Jose Garcia Villa helped fill the large theatre by bringing along all of his students. He too was gay, even though in Manila he had been married with children. He had been discovered by Edith Sitwell, the great English character and poet, who also was a Lesbian. The queer poetic connection at work, I suppose. Our friend James Purdy was also her protégé. His queerly romantic, amusing, and horrific stories and novels make him, to my mind, the greatest American writer of the end of the last century.

I’ve always felt that the monks of the Dark Ages who kept ancient literature alive must have let some of the Greek myths slip through the cracks. I wanted to restore a queer one. Howard Moss, who was gay, liked my poem “The Marriage of Dionysus and Apollo” but even as the long-time poetry editor of The New Yorker he felt he couldn’t get it past the magazine’s presiding editor Shawn. But it was soon taken by George Plimpton’s Paris Review and then, with slight revision, by the good old gay magazine Christopher Street. I was particularly happy to have written a rebuke to the Latin proverb post coitum triste that has long plagued lovers of sexual pleasure:

Every animal, man, or god,

After sex, sings in his blood.

A few years later I was at a World Poetry Conference where the organizers had the brilliant idea of pairing young poets and famous ones in the rooms provided by the Conference. I won Robert Duncan in the lottery and I remember a poor sexually inexperienced poet’s getting Allen Ginsberg and going petrified to bed with visions of getting fucked in the arse by that ardent and bearded older poet. Duncan was wearing a black arm-band and I wrongly assumed that someone like his lover Jess had recently died so I was especially solicitous of Helen Adam’s friend in the early part of the night. But when I hopped into bed over came Duncan with the obvious intention of getting screwed that night. Now he was the last person I would be sexually interested in and I was not practical enough to offer myself up for that particular form of networking—and, in fact, I was not even keen on the direction that New Directions poet’s work was taking.

A brief footnote: some time later he was a guest at a party at my West Side apartment. I have a disorderly collection of thousands of books, but the least chaotic section of my shelves is the poetry assemblage in my entrance hall. Before coming into the main party in the living-room Duncan spent half an hour going over every single book on those shelves, of course not finding his own among them. I was surprised that he didn’t just head out the door at once then.

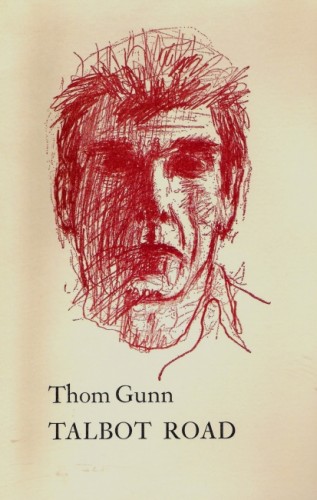

Now in San Francisco there was a much better poet (and who would not say a hotter one?), whom I would gladly have considered being fucked by: Thom Gunn. In fact when I got to know him and Helikon Press published his remarkable gay poem Talbot Road, I began an assault by letter with that intention, but he wouldn’t bite. Instead he added a snotty dig at younger poets in a new poem of his and though I did, and do, consider him the best Anglo-American poet of the last half century, I still felt I had to pull his leg. I invented a Lesbian poetess who had audited one of his poetry workshops at some mid-Western university and got a Lesbian friend to send him a sonnet in her elegant hand. It was essentially about Gunn standing before a series of paintings in the ancient Italian style of boy poets representing Christ dying on the Cross, I only remember the last couplet:

And though we hang by our swelling balls and thumbs,

Know what to do until the poet comes.

Postscript:

I must confess that the title of this piece and the end of the poem’s last line are not my original invention. It was the actual heading of an instruction sheet given out to the audience at a reading I once gave—in my native Boston, of course.

Facebook Comments