During a trip home to my native Memphis a few years ago, I was introduced to the photography of Jack Robinson. A gay Southerner whose meteoric rise in the 1960s and 70s was followed by a quarter-century of near-total obscurity, Robinson’s story immediately intrigued me, as did his unlikely rediscovery. During the last 25 years of his life, Robinson worked as an artist in a stained-glass studio, living alone in a Midtown Memphis high-rise and battling depression. He never shared with his employer or neighbors his glamorous past as a photographer of some of the most celebrated personalities of the twentieth-century. It wasn’t until many days after his death in 1997 that his employer ventured into his apartment and discovered an actual treasure chest of Robinson’s images—thousands of them. His work is now archived in a downtown gallery that bears his name.

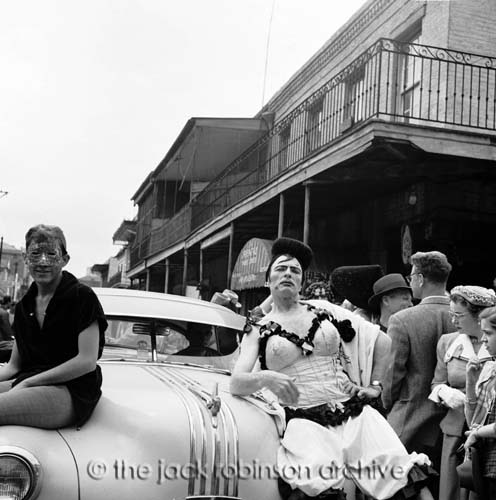

A native of Clarksdale, Mississippi, Robinson honed his camera skills in the early 1950s, documenting bohemian gay life in New Orleans’ French Quarter. A regular of Dixie’s Bar on Bourbon Street, a watering hole known for its literary clientele (Truman Capote, Tennessee Williams and Gore Vidal among them), Robinson documented the city’s gay cultural scene, and its involvement in Mardi Gras. His depictions of gay men in costume and in various states of drunken frivolity captured at the same time the joy and freedom that the French Quarter afforded as a reprieve from the repressive South.

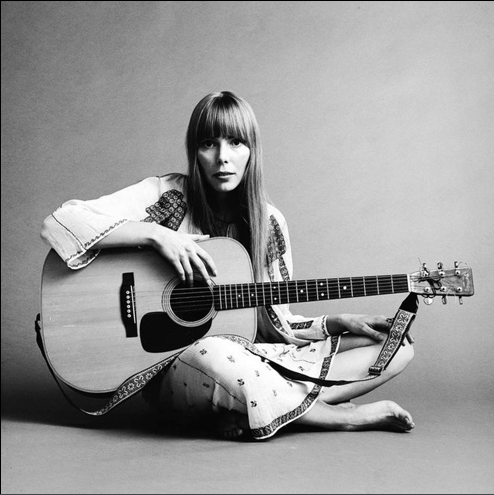

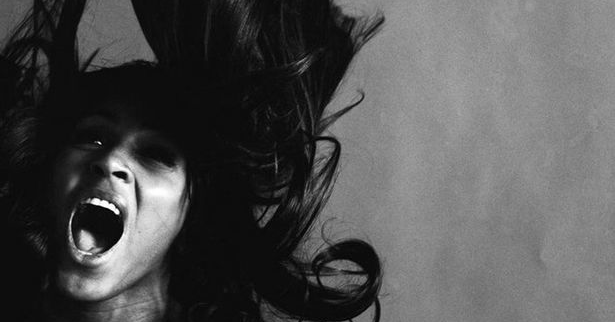

It was through his arts connections that Robinson met Betty Parsons, a New York-based art dealer who persuaded him to move north to pursue photography as a career. In New York, he caught the attention of Vogue editor Dianna Vreeland, and over the next decade at Vogue amassed an enormous body of work featuring many of the film, music and literary stars of the 1960s and early 70s—Andy Warhol, John Lennon, Elton John, Joni Mitchell, Jack Nicholson and Joe Dallesandro, to name just a few.

Joni Mitchell

Joni Mitchell

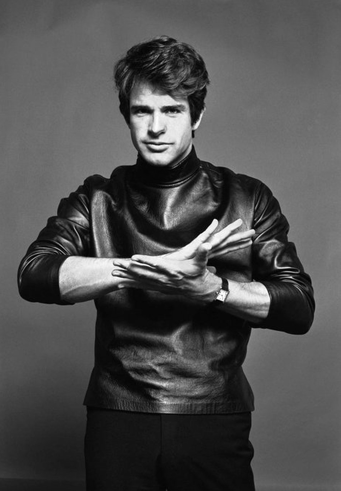

Some of Robinson’s photographs, perhaps, draw their wattage more from the star power on display than the strength of the picture itself. But other photos suggest an obvious and striking attraction to his subject. A queer sensibility radiates from many of his images: Warren Beatty sporting a fetishistic, high-neck leather garment, his mannerisms suggesting vulnerability and crackling with homoeroticism, or Clint Eastwood in a dainty knit sweater, leering suggestively toward the lens. Robinson’s numerous portraits of Dallesandro capture a more pensive young man than usually seen in the actor’s porno shots. The cumulative impact is stunning.

Warren Beatty

Warren Beatty

What makes Robinson’s photos all the more evocative is the fact that most were taken as the subjects were on the verge of notoriety. These were fresh faces: Elton John was just hitting America and the Who had recently released Tommy; Beatty had just starred in Bonnie and Clyde, and Nicholson was about to appear in Easy Rider.

In the late 60s, Robinson became a regular at Warhol’s Factory, and began struggling with the sort of drug and alcohol addiction so prevalent at that time and place. When Vreeland was fired from Vogue in 1971, Robinson began a serious downward spiral. With his commissions drying up, Robinson vacated his studio space and began selling off possessions to survive. He began drinking heavily. Only a year later he abandoned New York to return to his native South. He felt bitter and despondent, and was soon alcohol-dependent.

With the help of AA, Robinson was eventually able to get clean, and reinvented himself in Memphis as a local artist. Aside from his stained-glass work, his Memphis photography rivals William Eggleston’s in capturing the city’s rich texture. Still, Robinson kept his past a secret, for reasons that remain unclear. Was it the shame of a once-celebrated career in New York now over? Surely his lifelong tendency toward shyness played a part. But sharing his past might also have meant revealing his sexual orientation. Gay men like Robinson were used to masking their sexuality in the deeply religious, conservative south–hiding in plain sight, as gay Southerners often still do.

I have to admit that I wanted to find, in Robinson, some sort of validation—that here in Memphis a gay man was being celebrated. There are other gay artists, of course—Ira Sachs, Mark Doty—who have called Memphis home. But even today when the local press heralds the rebirth of what was the Memphis “gayborhood” of Midtown, our role in that rebirth is often neglected. Gay men and women make up a significant portion of the population in the Cooper Young area of Midtown, today the hippest quarter in the city. Decades before the yoga centers and the Beauty Shop-turned-eatery, gays were fixing up shotgun houses and filling dance clubs like Buddy’s. Today it is a mix of self-repression and what passes for Southern manners that hides our story from much of the city.

I admire those gay artists who have who have stayed in Memphis. Filmmaker Morgan Jon Fox’s documentaries (This Is What Love In Action Looks Like) and narrative features (Blue Citrus Hearts) are a reminder one does not need to leave Memphis to produce powerful, thought-provoking, gay-centric work.

My boyfriend and I have thought about one day returning to the South. I miss much about Memphis: her music, her manners, and her scrappiness. Part of me feels that as a young, politically-aware gay man I surrendered an important battle by leaving and escaping to San Francisco. Perhaps I should have stayed behind and fought the good fight–or at least helped run the LGBT film festival.

Friends matter more in the South, I believe. Perhaps when there are fewer surface possibilities people matter more. This is particularly true for gay men in the South. Before we began broadcasting our thoughts and desires to everyone via social media, we shared a special coded language with each other, a language that strengthened friendships born of similar desire and identity. One gets a sense of that fraternal connection in Robinson’s early New Orleans work. Passing over the photographs of the many notable figures, I settled on one photo: five gay friends walking through the Quarter during Mardi Gras in the late afternoon, past a neon sign that reads Gunga Den. They are replete in full carnival gear: hats, makeup, flasks in hand. It’s February 1952 and they are just beaming at Jack.

Facebook Comments