In mid-July, 1977, after a violent confrontation with his father, young Kevin Bentley lit out for San Francisco, that famous territory that beckoned thousands of gay men seeking a place where they could be accepted and meet each other. Unlike many of his fellow travelers, he kept a detailed diary of his day-to-day experiences, which usually consisted of plenty of good, hot, dirty sex. In 2002, Green Candy Press released Wild Animals I Have Known, which contains Bentley’s journals from 1977 to 1996. The book is a sharp, incisive, fascinating, and very sexy chronicle of real life in San Francisco. Though his sexual experiences are at the forefront of the narrative, the book takes a dramatic turn in the early 1980′s when Bentley contracts HIV, along with many of his friends. Since he was an asymptomatic case, Bentley survived the decade, but eventually witnessed the deaths of many friends and two of his longtime partners. Today, Bentley lives in San Francisco with Paul, his partner of 15 years. He still enjoys his sex life, and is still writing about it. I called Bentley at home to talk about the construction of his diaries, his influences, and the unique pleasure of reading real stories of our gay lives.

Adam Baran: You started writing the diaries that became Wild Animals I Have Known in 1977, right?

Kevin Bentley: The book starts in ’77. I was keeping diaries full-time beginning in college. They’re good for going back and reminding myself of what I’d forgotten. There was a lot of sex in those. But I wasn’t a good enough writer then. I could delve into them for circumstance. By 1977, my experience added up. I was so immersed in reading and writing, and then I worked at a bookstore and I read, read, read. I think that’s when my diaries started getting better.

Is the diary your favorite type of literature?

Oh yes, that’s my thing entirely: autobiographies, biographies, diaries and novels that are written as diaries. When I was at the height of writing the diaries that became Wild Animals I Have Known in the late ’70s and early ’80s, a book came out called The Secret Diaries of Adrian Mole, and there ended up being a lot of sequels to it. It was like the prose predecessor of that Diary of A Wimpy Kid. But there was sex stuff in it. It was a kid writing about beating off. That was very much in my mind when I wrote my diaries. I liked the combination of sexually frank commentary and wide-eyed sarcasm.

Was there other sexually frank literature that inspired you?

I was very into those Boyd McDonald Straight-To-Hell chapbooks like Flesh, Meat, Juice—sex volumes that were very “in your face” and raw, clearly came from real people. Usually the height of bad writing, but they were these very real accounts of people’s sex lives. When I first hooked up with my partner Paul whom I’ve been with for the last 15 years now, one of the things we discovered we had in common was totally falling apart copies of those chapbooks held together with rubber bands. He had the same ones I had. We had both worn those out.

When I write my journal, it’s terribly hard to know what I’m writing. Your writing makes it seem like you had so much knowledge and wit about what you were going through even then. Is that a result of your being able to edit and shape it—or is that just how you wrote it?

I can open up an old notebook and show you how close to verbatim most of it is. What I did was essentially taking the best bits and following certain people who have been life-long acquaintances and friends and leaving out people who were just there in passing. So it had continual characters.

Did you take any inspiration from either John Rechy’s books (City of Night, Numbers, Sexual Outlaw) or Renaud Camus (Tricks)? They both wrote diaristic accounts of their sexual exploits.

I kinda took inspiration from Rechy. He’s a forbearer. Do I think he’s a good writer? I can’t read a line of his without cringing. I do find him a fascinating figure, and I applaud him for doing what he’s doing so early. He’s from my hometown. My mother was in the same class as him and she was very tight-lipped and upset because his book was in the library. As for Tricks, I remember it coming out when I was at the bookstore I worked at. I remember that book seeming a little grim to me. It’s very kind of unemotional and very cold. And I think I was always aware—and that was part of what I tried to tone down in my book. Not being too…

Fatalistic?

Not to be too over-the-top with the emotions because there was always a lot of emotion for me. Even when it was the most overnight, transient trick.

That’s interesting, because a lot of what this section is about is the choices that people who make autobiographical work make to tell their story to other people. You’re saying you made a conscious choice to edit out emotions?

I wanted the diaries to be entertaining and readable versus the worst kind of artless introspection. The Adrian Mole books had a certain smarty pants tone that I liked and I always thought my diary would be saved by that—and good editing. I decided that reading about bad break-ups might not be so entertaining for other people. It was a conscious marketing and artistic decision. When you’re working at home and weeping over the phone not ringing from one boyfriend or the other, you’re not necessarily at your writing best or at least in my case. There are only so many people who would want to read a diary by a non-famous person. Finding an audience is tough. So I had every reason to put the sex in it and I was very happy to include that stuff.

Were you a fan of the Ned Rorem diaries?

Love, love, love. I first heard of him when those were re-issued by Northpoint Press in beautiful, oversized soft-band editions with these gorgeous pictures of young Ned on the cover. I ate them up. I thought they were the most wonderful things ever. And as he goes on in his age, I’ve been very fascinated to read his reflections on still being sexual and getting older, and looking at himself in the mirror, and friends dying. It’s one of many good reasons to have friends who are more than just your own age, so that you know some people who are a little further down the road from you so that you kind of get an example or two.

Along that vein, do you think we as gay men appreciate reading about our real lives because we’re a minority? Are we just looking for things to emulate because there’s so little out there?

Both. I think it’s sort of true for all minorities. But, you know, maybe for us, particularly, because what’s more close to the bone than sexuality and love? What I’ve always been looking for is reflections of my experience. We all get bombarded everyday with all of our art, which is 99% in straight people’s experience. So, you know, that first thrill of reading that wonderful literary Edmund White novel that was about our experience. Even if it wasn’t just like my life, at least it was a gay experience. I’ve always looked for that. You can still read a heterosexual intimacy experience and relate. It’s not that we can’t juxtapose our emotions to straight scenarios in art, but how much more important is hearing our own story? It’s all I can write. I, honestly, am very much in the part-timer, dilettante thing. I don’t think I’m ever going to produce a great novel. I don’t write everyday, except in my diary. But what’s important to me to try to write about is stuff that’s happened in my life that I want to make sense of and that I want to make something artful out of that will give it more meaning, you know. Writing about the two partners I had who died was just the most important thing in the world to me. It wasn’t enough to just get down the details of them for my own sake. I wanted to put them in something that people would read because it was sad and beautiful, and then I would have kept them alive in that way. I knew that they would appreciate it, that they would admire the writing that exposed very personal things about them. That’s why I was driven to write the things that I have done, I think. The large part is that feeling, wanting to make some kind of meaning to stuff that otherwise just goes away.

One of the things that I was curious about—in the book you had someone telling you that they didn’t want to be included in your diary. I was surprised that people knew you were writing it.

[Laughs] Yeah. All of my friends knew. That particular individual, at that time, I would’ve done anything I could have to get him to continue to have sex with me, so one of the ways that I did was show him what I had written in my diary about the last time we had sex. He would be rather comically appalled by it and yet, you know, put it aside and suggest that we do something about the boner we had now. So it was kind of a way of titillating him.

It fed his ego as well. He was a character suddenly in your life story. It seems like such a far cry from today’s blog, Twitter, X-Tube kind of world.

My partner Paul once asked me,“Who are all these twenty-year-olds putting themselves on X-tube?” And I said, “Honey, they’re us.” If he and I were that age, we would be doing this. That’s what I think: “What would my life have been like in this age and time?” I’m sure that that’s probably what I’d be pursuing. But being in a book is like hiding in plain sight. Not many people will bother to pick up a book and read a page, so it’s pretty easy to hide. [Laughs].

Were there things you left out because they were just too personal? Or to protect someone?

I don’t think so. If it helped with the book… I know that there were things that were a little bit embarrassing to me that I included. I went back looking the other day because it was the 30th anniversary about the first New York Times article about the discovery of the “gay cancer.” And I always go through this with one of these anniversaries where I think, “Oh, what do my diaries say about that thing?” But it took a year after that article for it to make an appearance in my journal. I knew about it, but I think that I had a kind of superstitious feeling, like if I talk about it I might get it. I didn’t even want to write about what was going on at that first point because I wanted it to stay far, far away from me. There are things in the diaries about that that embarrass me.

One last thing. I’m asking people to respond to this quote by Quentin Crisp: “An autobiography is an obituary in serialized form with the last part missing.”

That’s, certainly, all of my emphasis. Getting all this down because I want my experience to outlast me. Not just because I was here but because I thought about it and I think there’s some meaning there and I want to preserve that. You’re writing your obituary, getting it all down, before someone else writes it.

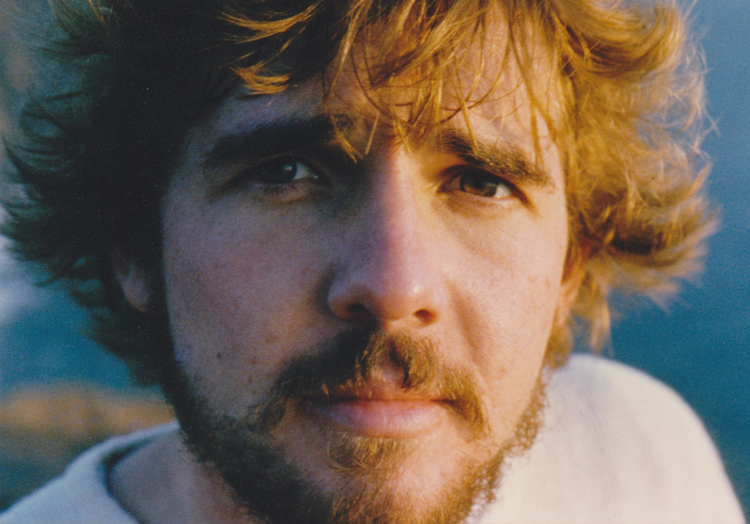

Kevin Bentley (center) with friends, 1981

Facebook Comments