The second installment of poet William Leo Coakley’s autobiographical essay about his life with actor and writer Robin Prising takes us from the couple’s move to West 4th street to Jane street, then from New York to Rome. Along the way scores of legends make appearances – Jack Wrangler, George Barker, Djuna Barnes, James Merrill, Franz Kline and Iris Tree, to name but a few. Check back next week for the conclusion!

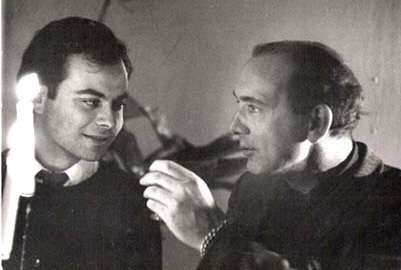

When I first came down from Harvard to the Village I lived at the corner of West 4th and West 12th (only in New York, I thought). I remember sauntering hand in hand through the pre-Stonewall Village with my charismatic mentor and friend the English poet George Barker. He was 99% straight, having many mistresses and more children, but the soldiers and sailors of World War II had been his lovers too and he was the body in Willard Maas’ 1943 film Geography of the Body. He had such dynamic energy that just walking and talking with him was a sexual experience. “Go and do it, Baby,” he urged me on to poetry, “Go and do it, Dirt.” He said that to strengthen my poetry I must listen to the “compulsive recurrence in the little matter of fucking.” I later found out that Robin had independently known him in the 1950s in London. There is a fabulous picture of the two of them in the 50s staring at each other over cigarette smoke (that lost aphrodisiac), the sexual vibrations, never consummated, alive in the air between them. When we lived in London and Europe in the mid-60s George was amazed to discover we had found each other and that cemented our life-long friendship with him. When he visited us in New York around 1966 we stopped by the writers’ bar the White Horse Tavern for a drink—and were barred at the door by a bruiser of a bouncer: we were not accompanied by “ladies.” The police were cracking down on gays in bars. George told him to go fuck himself, pulled out his wallet with pictures of his was it 13? children—and put a curse on the dive. It must have worked: the place is foolishly known as the bar where Dylan Thomas drank himself to death and now only tourists congregate there to stare at tourists.

Robin and George Barker, London 1950s, photo by Peter Nicholson

By 1960 I moved to Jane Street to a straight Harvard friend’s tiny studio looking out through French doors to a shared courtyard. There was no difficulty in my fucking a boy on one side of the narrow room, while he was at a girl on the other. I remember one day, though, when I was alone with my first lover Parker, we were happily screwing and suddenly there was a great rapping on the French doors—we were sure it was the sex police. It only turned out to be the harpsichord-maker across the way with a minor crisis of his own; but, coitus interruptus, we had to shuffle over to a bar for a while to recover.

On weekends, say, we might have some kind of sex four or five times a day and night, while still managing to work and to hear concerts and plays or head to the ever-present cinema, which I thought should begin with an S. As we proceeded into the sexual maelstrom of New York we discovered we were receiving the blessings of a gift which was called the Apostolic Succession—sleeping with men who had slept with men who had slept with a whole pantheon of queers in history: Byron, Rimbaud, Verlaine, Whitman, Wilde, Gide, Bosie, Noël Coward, Tennessee Williams, and even Jack Kerouac, Gore Vidal, and Ned Rorem as we came closer to our own generation. I seem to remember that an important link in this chain of sex was a San Franciscan named Gavin Arthur, direct descendant of the 21st President. Bertha was engaged in her own historical bent. She followed round the Village the reclusive and elegantly caped Djuna Barnes and lay violets on her doorstep in the beautiful bohemian enclave of Patchin Place.

When the affair with Parker was over, I would often head uptown to my gym to indulge in my sexual fantasies more vigorously than my exercises. It was mainly straight but there were plenty of gay dancers, actors, musicians, and agents (and should I add writers?). In the sauna and steam room, we could sometimes have quick sex or at least a prelude to a meeting later that night. I usually focussed on guys like the boy with one leg, his beauty unmarred, but he soon left for San Francisco. Didn’t they all? I should mention my “affair” with Jack Wrangler. A few years younger than I (but dead already, alas), to my mind he was a quiet, almost shy boy, deliciously trim but intriguing for always hiding his cock, even when showering or dressing. Gradually, as we got to know and like each other, we would retire to the back booths of local bars, holding hands and kissing and mouthing romantic sweet nothings to each other—but we never had sex. I was just starting off with Robin, and he with the popular singer Margaret Whiting, whom he eventually married. How my friends laughed at my naïve foolishness when he became a straight and gay porn star later and they found out I had never even seen his cock, let alone made good use of it.

But I was not being a monk, I remember one exciting night in the pool, at the deep end, when an erotic photographer I knew improved his skills by blowing me under water. I mean, he was under water, incredibly never rising up for air. I tried to keep a calm face and come as quickly as possible, so I wouldn’t end up with a drowned man at my heels or the management down on me too. For research only, of course, I had just a whiff of the wildness of the Baths that engulfed the gay 70s, the ones on St Mark’s Place and the Ansonia’s Continental nearer to my future home.

But I mainly stayed in the Village and my crowd of artists and writers would usually go to the Cedar first and I loved just listening to the great artists about like de Kooning, but it was the ruggedly handsome and personable Franz Kline who most appealed to me—and he also liked poetry. He would sometimes take me for a nightcap to his spare place in 14th Street nearby, where his own collection of his stark and vivid images seared, and still sear, into my imagination. He too was soon to die.

My favorite Cedar habitué was Jimmy Spicer, who, queer genealogy being somewhat confused, was possibly once a lover of James Merrill’s but definitely, recently, a lover of one of Merrill’s old lovers, who expressed his devotion by removing Jimmy’s big toe in a wood-chopping accident at his country place.

Jimmy’s special trick was to promise to go home that night with any fellow who would let him drink his piss. Well, there were takers, and in they would go to the john and out came Jimmy with a foaming mug. Now the piss of us young poets and artists was probably 65 % beer, though I can’t say so much for the stars of the Cedar, who, in any case, were not apt to be tested.

When Robin’s and my affair began, Jimmy proved a friend in need. Robin couldn’t take me to his place, except the few times his lover was away, and he had no intention of being on display in my straight friend’s little studio. So each night for weeks, after hasty meals, we would retire to Jimmy’s 4th Avenue apartment and his Imperial bed like something out of the Arabian Nights, a perfect place to fuck for hours, and you could say that, unlike many couples straight and gay, we would continue to do so for 48 years. Jimmy, of course, was quite content to play all night at the Cedar. Alas, he too died before his time, after whittling down the amusing diaries of the Living Theatre’s Judith Malina to publishable size. Robin made me tell his lover that they were breaking up. He figured that if I hadn’t the balls to do so, he wouldn’t be interested in me. Well, in 1961 on April 1 (what day more apt?), we finally moved in together.

I soon found out that Parker, after we had broken up, quickly had sex with both Robin and, separately, with Robin’s then lover. In any case we all remained friends. Once years later at a late-night party that had fizzled out to a few gay guys reminiscing over their last drinks, the door bell rang and a woman friend from work, who had been to another party, staggered in drunk. After reinforcing her with some hot tea, we boys continued our gossip and suddenly Parker, in his delectable Southern accent, blurted out: “You probably don’t realize it but Willie was the first maaan who ever fuuuucked me!” My poor friend dropped her tea-cup all over the floor.

Willie and Robin, London 1964

For some strange reason I happen to like sex and, indeed, Robin did too. I should add that he and I were both Versatile, as they say in Morocco and Adam4Adam; and that probably contributed to the longevity of our sex life and our love life. And we believed that we should be absolutely open about those lives. The role-rigidity that then characterized many of the older queers had escaped us. As your mother surely has told you, there is nothing so boring as a complete top—or a complete bottom.

Of course what held us together ultimately was our common interest in literature, art, music, and politics. We both despised the blood-drenched and homophobic religions of the monotheists but Robin was essentially more spiritual than I and he was saddened that I was a complete atheist and didn’t believe we would meet in an afterlife.

In his youth Robin had been a prisoner of war of the Japanese in the Philippines during World War II and he witnessed the destruction of his city of Manila by the Japanese and the American armies, with 100,000 Filipino civilians dead around him. In the mid-70s Manila, Goodbye, the story of his childhood before and during the war, was published in England and the States and he was surprised that the Catholics, well a liberal branch of them, gave his book the Christopher Award for representing “the highest values of the human spirit.” When he came to America he had no intention of letting anyone else rule his life or censor his work and I heartily agreed with him. At 15 he went to New York with his first lover Bill Quinn, who was also a Harvard man, and he studied and acted with Eva Le Gallienne. Miss Le Gallienne, as she was always called, was then involved with the Shakespearean director Margaret Webster. The two great ladies of the theatre took him under their wings but it was Miss Le Gallienne, especially when they were living together on tour, who talked with Robin often of the pleasures and dangers of being homosexual in America and in the theatre.

Robin, though, remembering the horrors he had witnessed, also devoted much of his time to work in the pacifist movement, and he often spoke against war on the streets of New York or even in the interior cities of the lethal war factories.

But as the Vietnam War was beginning to escalate we had the opportunity to leave America for Europe. The sale of our books and small inheritances after the death of our parents (I think mine was 30 pieces of silver) enabled us to do so on a pittance, as was still possible, particularly in Italy and Greece. We lived in London, Paris, and Florence, and, though intending to head down to von Gloeden’s Taormina, had to settle in Rome, where one could live more cheaply and find work if need be—and in that city of history and art, there was something different to see every day. We luckily ran into Robin’s old friend the English actress Iris Tree, whom he had acted with and lived with briefly in California. Her apartment was in the house above the Spanish Steps where Keats had died and I’m quite sure she was the model for Mrs Stone in Tennessee Williams’s Roman Spring. When Robin knew her she was married to the tall and aristocratic German Count Friedrich Ledebur, who oddly enough played the tattooed Queequeg in the film of Moby Dick (and Iris a Bible woman). They were separated now and Iris’s constant companion on the streets of Rome was her sleek black Belgian sheepdog Aguri (we adopted his gorgeous replica Harfleur on our return to the States). You can still see them today, as Iris played the Poetess in La Dolce Vita, her dog at her feet. He outlived her and spent his last luxurious days in the great house of her friends the French Rothschilds. With Iris’s connections we were able to find extra work at Cinecittà in spaghetti Westerns and interminable Roman epics. We never found ourselves in the few films that reached the American cinema theatres, but we were able to extend our stay in Italy another six months.

Facebook Comments